Subrata Mitra, Satyajit Ray’s cameraman, described by Time as one of the all-time great cinematographers, at the Convocation of the FTII (From The Indian Post, Thursday, October 12, 1989)

Dear Students—young filmmaker friends,

I feel honoured to have this opportunity to speak to you on this important day in your life. I am told that the governing council felt that the convocation address this time should be made by a technician. So, I think I can take the liberty of sounding more like a technician, or to be precise, more like a cinematographer. In the process, if I sound too personal and somewhat out of tune for this occasion, I hope you will understand whatever I say, I believe is also important for you to know.

I feel honoured to have this opportunity to speak to you on this important day in your life. I am told that the governing council felt that the convocation address this time should be made by a technician. So, I think I can take the liberty of sounding more like a technician, or to be precise, more like a cinematographer. In the process, if I sound too personal and somewhat out of tune for this occasion, I hope you will understand whatever I say, I believe is also important for you to know.

For many years, I have been associated with the Institute in various ways—as a member of the academic council, and before that, as a member of the advisory committee. I remember that every time I cane for a meeting, I had to extend my stay here. The students would attack me from all directions with their innumerable questions and inquiries regarding filmmaking. I started taking classes, playing the role of a teacher, which I never thought I would do. I conducted workshops, trying to tell them literally everything I knew. These lessons were not confined to the classrooms alone—the discussions continued in my room, under the wisdom tree, and in the restaurants. It was really a long and never-ending process which I thoroughly enjoyed.

I thought I understood their problems very well. I knew exactly where they would get stuck and exactly how helpless they felt, because I had gone through all this myself, but without any help from anywhere. I remember my own days as a beginner.

My beginning, however, was very different from yours. I had to start as a full-fledged cameraman with little knowledge and no experience at all. As I was nobody’s assistant, I did not even have the opportunity to handle a movie-camera before I shot my first film. And I was not privileged like you—I was not taught in a film school. I had no other way but to be a self-taught cameraman. I had to spend many sleepless nights trying to solve problems which I knew I would face the next day. I had to invent simple things which even a first-year student here would know, and discover things for myself which already existed for others. But in this process, I also invented my own methods which became indispensable to me and also to many others. This I would not have achieved if I were not ignorant. Actually, my ignorance was a blessing in many ways.

My beginning, however, was very different from yours. I had to start as a full-fledged cameraman with little knowledge and no experience at all. As I was nobody’s assistant, I did not even have the opportunity to handle a movie-camera before I shot my first film. And I was not privileged like you—I was not taught in a film school. I had no other way but to be a self-taught cameraman. I had to spend many sleepless nights trying to solve problems which I knew I would face the next day. I had to invent simple things which even a first-year student here would know, and discover things for myself which already existed for others. But in this process, I also invented my own methods which became indispensable to me and also to many others. This I would not have achieved if I were not ignorant. Actually, my ignorance was a blessing in many ways.

I may assure you that walking out of this institute and walking into a new world, you will have to be self-taught—as much as I was. So get ready to learn many more things than you have learnt here at the institute. Yes, you are much better equipped than I was, because during your stay here you have had enormous and unique assistance from many quarters—from films, books, journals, modern sophisticated equipment and the teachers here. But try to remain a student of cinema for the rest of your life.

I have come across many types of students here. Many of them are really sincere and fully committed. I can see that in every year there are at least a few students because of whom my long journey here fromCalcuttawas justified and my stay here made worthwhile. It is always rewarding later, when after a few years, you suddenly discover these students in the role of creative and successful filmmakers. I am sure the teachers in this institute have experienced this satisfaction many times.

Today you are being initiated into a very special kind of religion. You are going out to face the world. If I restrict myself only to a pleasant address on this occasion, I will be doing an injustice to you.

Yes, I have always felt that filmmaking was a religion. I left college and was lucky to be able to watch two great filmmakers working together—Jean Renoir and Claude Renoir. I watched very carefully the shooting of films every day, and took notes. Actually, I did not know what I was doing and I do not think I learnt much about filmmaking as such. But I learnt one thing from these masters for sure. I realised that filmmaking was like a religion to them and they were completely dedicated to it. As I watched these two great masters at work, I also got initiated into this religion.

But today I realise with great pain that there are unholy forces, much stronger and too many in number, acting against my religion. I know—of late I have been feeling quite frustrated and helpless, and many things are becoming pointless to me. Painfully do I realize that many a thing which I immensely enjoyed is fast losing its charm.

When we make a film, we put all our efforts to improve on the quality. It is also true that we cannot achieve what we aim for. But we are more or less happy with what we finally get. Striving through various stages of filmmaking, we ultimately get a print which embodies all our thoughts and efforts. By the time we reach this stage we are completely exhausted, but full of hope—because we have not spared ourselves any effort.

But unfortunately, this is also the stage when we lose control over our own films. To reach our audience, our films pass through all kinds of people who do not have, in most cases, any love for cinema or for its aesthetics. Ultimately the fate of a film depends on the mercy of the distributor, the theatre owner and the projectionist. The amount of callousness, ignorance or even dishonesty prevailing in these areas is appalling. You can consider yourselves extremely lucky if your film is released in a proper theatre, and not in a slaughter house.

But unfortunately, this is also the stage when we lose control over our own films. To reach our audience, our films pass through all kinds of people who do not have, in most cases, any love for cinema or for its aesthetics. Ultimately the fate of a film depends on the mercy of the distributor, the theatre owner and the projectionist. The amount of callousness, ignorance or even dishonesty prevailing in these areas is appalling. You can consider yourselves extremely lucky if your film is released in a proper theatre, and not in a slaughter house.

To prove my point I will tell you that some time ago, before the release of my latest film, I made a survey of a number of theatres inBombay. The survey, which I conducted meticulously, was an eye-opener to me and to my colleagues who accompanied me. It was found that projection standards varied from theatre to theatre and were much below the recommended international standard.

To give you my findings in short, the reflectances measured at the screens were 2 to 4 full stops below the recommended standard. The conditions of theatres inCalcuttaand in many other places are even worse. On top of that, in order to save electricity, the projectors are made to run at lower amperage, using substandard carbon arcs, thus grossly damaging the visual quality of the films. For the renewal of their licenses, I suppose, the theatres are periodically inspected by government inspectors for proper ventilation, seating and sanitary facilities etc. But the projection and the sound system, the two most essential things, are never considered important enough to be checked.

It is also pathetic to note that the various cinematographers’ associations and similar organisations are completely indifferent to this major obstacle between the filmmakers and the filmgoers.

We try our best, putting in all pour efforts when we make our films, but little do we realise that everything would be meaningless at this last stage. You would agree that taking out a single net from a light or putting out one or another would be totally pointless when the film is to be shown on a projector running 4 stops below the recommended standard. I am not saying these things for people who do not take risks in their work and always play safe. But this should concern everyone who is interested in capturing subtle nuances and delicate artistic quality in his work.

This is a very serious obstacle, say, for the cinematographer, whose work depends on the subtle tints of a rainy day or dawn or dusk—the drama present in the scorching sun at high noon or the poetry of a cloudy day. I must make it very clear that when the visual atmosphere or mood of a film is damaged for any reason, it is not the concern of the cameraman only. In the ultimate analysis, such lapses are an assault on cinema and everybody involved in the film should feel upset. It is everybody’s concern. In this connection. I shall narrate an incident to you. It took place inBombayin 1984 during the Filmotsav.

Bergman’s Cries and Whispers had just begun inside the theatre—before which the well-known actors Erland Josephson and Aina Bellis of the Swedish Film Institute were to be presented on the stage. Everybody was inside and the hall was fully packed. I was sitting alone in the lobby, holding a cup of coffee. This was one of my favourite films and I had always admired its exquisite camera work. I had already seen the film 7 times before—whenever I got the opportunity and almost every time I came to the institute. In order to save the original print, the Archives here had made an indigenous print for future shows and circulation.

And from then on I had stopped seeing the film as this copy did not have that quality for which I admire Nykvist. And I did not want to ruin the impressions which were in my mind. This was also the reason why I was sitting alone in the lobby, not watching my favourite film. Suddenly, I found Erland Josephson and Aina Bellis rushing out of the theatre, trying to find the way to the projection booth. They were very upset as they thought there was something terribly wrong with the projection.

And from then on I had stopped seeing the film as this copy did not have that quality for which I admire Nykvist. And I did not want to ruin the impressions which were in my mind. This was also the reason why I was sitting alone in the lobby, not watching my favourite film. Suddenly, I found Erland Josephson and Aina Bellis rushing out of the theatre, trying to find the way to the projection booth. They were very upset as they thought there was something terribly wrong with the projection.

But this time the theatre-projectionist was not the culprit. I introduced myself, explaining to them the real reason, and they were convinced that nothing could be done. We went down for coffee and for a very long chat. I do not know how Nykvist or Bergman would have reacted if they were there but I was deeply moved to note that an actor was very much disturbed because the visual quality of his film was damaged. Not only was the legendary Nykvist wronged, but the viewers of an international film festival were deprived of a unique visual experience.

But frankly speaking, I do not understand our filmgoers and the so-called film-lovers either. Why did they not react at all or complain when daylight from four doors was constantly hitting the screen in the main theatre in Hyderabad—that too during an international film festival? The theatre management was indifferent even when complaints were made and so were the festival authorities. This went on for four or five days, ruining the excellent camera work of many films. When lakhs of rupees were spent for fireworks and beautifying the city for this occasion, the exquisite visuals of films from abroad suffered.

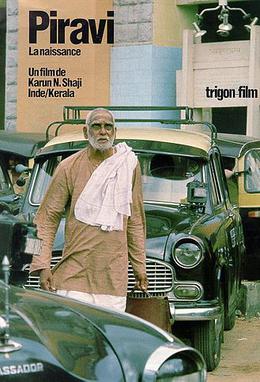

On the 11th of June this year, like millions of viewers in India, I eagerly sat before my TVset to watch the all-India premier of Piravi, which received the national award for the best feature film this year, and which I had seen inDelhi earlier. As you know, the film is directed by Shajij, the well-known cinematographer and I thought it was very well photographed by an ex-student of this institute—Sunny Joseph. But I could hardly watch the film! In utter disgust, like many others, I had to switch off my TV set, Lack of professionalism was evident from the very beginning of the telecast and I would say that it was a dreadful disaster. If this is the ultimate fate of a film, we probably do not need an institute like this to train technicians.

On the 11th of June this year, like millions of viewers in India, I eagerly sat before my TVset to watch the all-India premier of Piravi, which received the national award for the best feature film this year, and which I had seen inDelhi earlier. As you know, the film is directed by Shajij, the well-known cinematographer and I thought it was very well photographed by an ex-student of this institute—Sunny Joseph. But I could hardly watch the film! In utter disgust, like many others, I had to switch off my TV set, Lack of professionalism was evident from the very beginning of the telecast and I would say that it was a dreadful disaster. If this is the ultimate fate of a film, we probably do not need an institute like this to train technicians.

I was not able to see the film a second time—but sitting inCalcutta, I could almost see the tears in Shaji’s and Sunny Joseph’s eyes. They could not cross the last hurdle, for no fault of theirs. My sympathy goes out particularly to Joseph as he had just started out on his career, and I am sure that this was a big event in his life. I would like to know who should be held responsible for this disaster. Is it not a crime to crush the dreams of some able filmmakers and to present a very distorted version of a very well-made film to millions of viewers? As you know, this has happened many times in the past and this will go on happening in the future if we remain callous and inactive. Tomorrow it could very well be you who will suffer.

While I was typing out this convocation address, it was announced that one of my films would be telecast the next day. It came as a death sentence to me. But I never imagined it could be so painful. It was like some medieval torture that will persist for the rest of my life. Those who have seen this film earlier and also this telecast would understand what I mean. Most of the film could not be seen and it looked like a sixth generation video copy.

If it was a bad print or a bad tape or substandard photography, then I think Doordarshan should not have telecast it. Is it not important to check if a programme is technically qualified before it is telecast to millions of viewers?

But that is not all. How can I stop here without mentioning our National Film Development Corporation and the Film Archives of India? It is not only Nykvist or Sunny Joseph who suffer in this country. The NFDC and the Archives too have their share in contribution to this indifference and injustice. The NFDC continues to circulate terrible copies of foreign films. These copies, like counterfeit coins, are meant for circulation in the market, the ethics and technical codes of filmmaking being ignored. Circulation is for educating our people and to create an awareness of good cinema. But it has become a colossal farce and an offence which goes unprotested.

I promise you, I am not trying to be fastidious. Anyone who has seen a film in its original form, say, during an international film festival and later the NFDC version would vouch for me. Compare the NFDC prints of Mephisto, Lacemaker, Mona Lisa, My First Wife, Fanny and Alexander, and many others and their original prints, and you would agree that these films have been butchered. It is really painful to have to accept that the people who run the NFDC are so insensitive as not to see this difference or that they do not consider it a crime to assault the aesthetics of this wonderful art.

It would be relevant in this context to ask about the role of the Film Archives of ndia. Is it supposed to preserve distorted versions of good films? The version of The Passion of Joan of Arc which I saw the other day in Calcutta, was neither Carl Dreyer’s nor Rudolph Matte’s creation. I cannot find words enough to express the difference between this print an the one I saw in the early sixties of this all-time classic. Is this print going to be preserved for the future? Not only is the excellence of the original missing, but what is presented to the viewers is totally unacceptable by any standard. Are future generations going to evaluate these masters with this print?

This has been the fate of many a good film including mine. Otherwise, why do I feel embarrassed these days to see my own films? What has been preserved in the Archives is definitely not my work. Is it not a gross injustice to the filmmaker? There are prints of Pather Panchali in circulation, which give the impression that the film was shot with sound film—while the tattered negative of the film, which supposedly putIndiaon the map of world cinema, has been rotting for years in a government godown inCalcutta. Perhaps this negative should have been restored and preserved here in the Archives.

This has been the fate of many a good film including mine. Otherwise, why do I feel embarrassed these days to see my own films? What has been preserved in the Archives is definitely not my work. Is it not a gross injustice to the filmmaker? There are prints of Pather Panchali in circulation, which give the impression that the film was shot with sound film—while the tattered negative of the film, which supposedly putIndiaon the map of world cinema, has been rotting for years in a government godown inCalcutta. Perhaps this negative should have been restored and preserved here in the Archives.

Dear students, I have spoken enough and I am sorry if I have sounded out of tune for this occasion. But as I consider you my near and dear ones, I do not want you to suffer the frustration and bitterness I have gone through, whether you are a cameraman, a sound recordist, an editor or a director. In the interests of cinema and its aesthetics, I want you to fight against these evils, to protest against such colossal callousness and lack of professionalism. I want you to feel disturbed, because unless you are disturbed you will not have the urge to fight against these forces. Do not spare any effort in striving for the highest standards, and let not quality vanish from this country forever.